Which Type of Solar Panel Is Best?

For most homes, monocrystalline panels are the top choice due to high efficiency (22%+), long life (25+ years), and great space efficiency. For large commercial roofs, less efficient but more affordable polycrystalline panels can be a smart value.

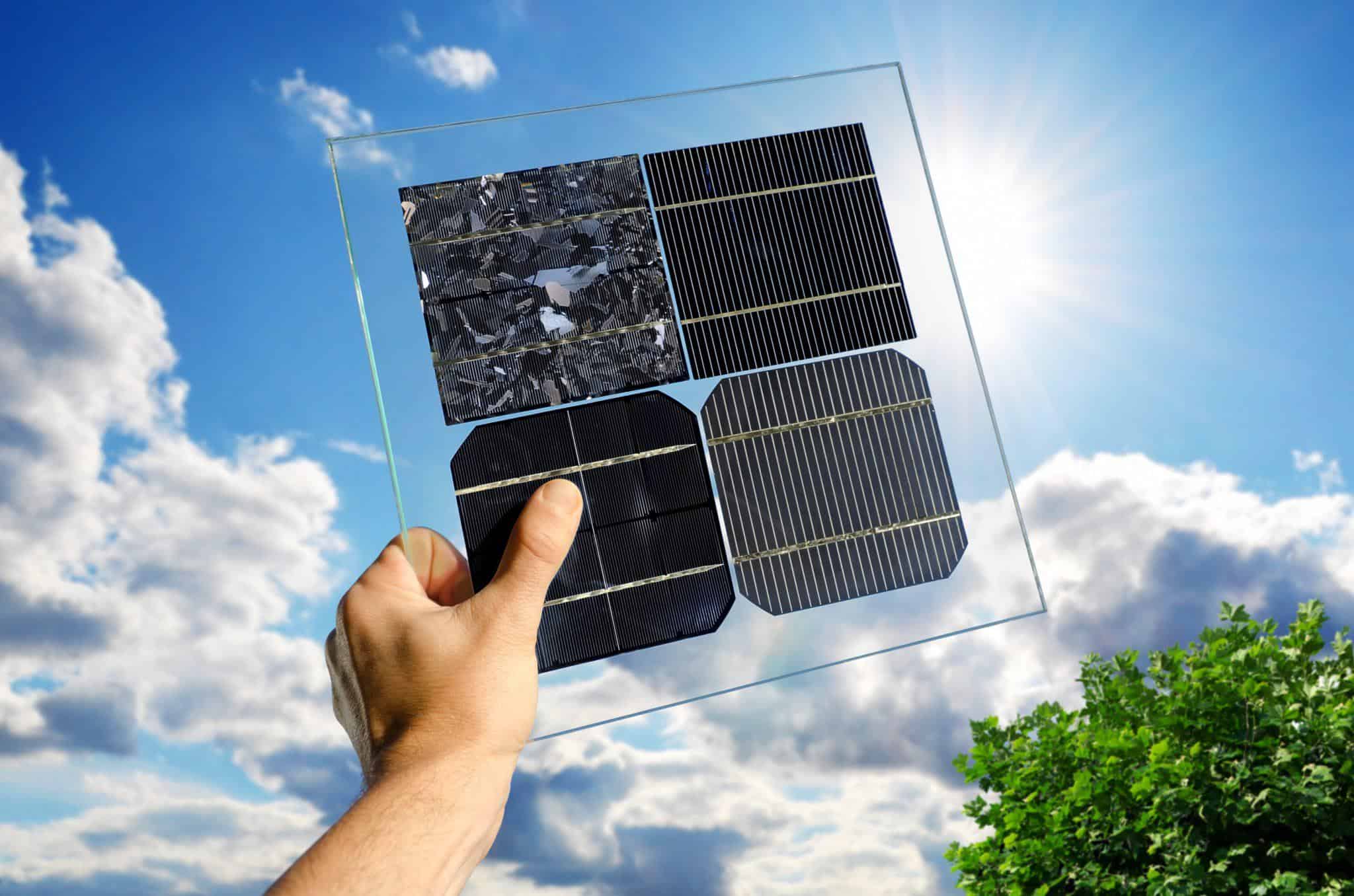

Solar Panel Types

Monocrystalline panels, made from a single, pure silicon crystal, are the premium option, typically converting over 22% of sunlight into electricity, with high-end models now pushing 24% efficiency. Polycrystalline panels, with their recognizable blue, speckled look, are a popular mid-range choice, with efficiency rates generally sitting between 15% and 17%.

A standard 60-cell residential monocrystalline panel typically produces between 350 and 400 watts of power. However, this performance comes at a cost; the complex production makes them about 20-30% more expensive per panel than polycrystalline options. They are also easily identifiable by their uniform black color and rounded cell edges. Most manufacturers back their monocrystalline panels with a 25- to 30-year performance warranty, guaranteeing they will still produce at least 85-92% of their original output after that period.

In contrast, polycrystalline panels are created by melting multiple silicon fragments together in a mold. This process is faster and creates less waste, leading to a lower upfront cost, often 0.10 to 0.15 less per watt than monocrystalline. The trade-off is the less-pure silicon structure, which results in lower efficiency, typically capping out around 17-18% for current models.

For example, a system requiring 20 monocrystalline panels might need 22 or 23 polycrystalline panels to hit the same kilowatt-hour production target. They have a characteristic blue, speckled appearance and square cells without rounded corners. Their degradation rates are similar to monocrystalline, with warranties also spanning 25 years.

Monocrystalline

While they represent a higher initial investment—often 10-20% more per panel than polycrystalline alternatives—their superior energy density can be the smarter long-term financial decision, especially when your available space is limited. Modern monocrystalline panels, particularly those using PERC (Passivated Emitter and Rear Cell) or half-cut cell technology, routinely achieve conversion efficiencies between 22% and 24%, with laboratory models pushing beyond 26%.

Monocrystalline panels typically have a temperature coefficient of around -0.30% to -0.35% per degree Celsius above the standard test temperature of 25°C (77°F). On a hot summer day where the panel surface temperature reaches 65°C (149°F), that's a 40°C increase, leading to a power reduction of roughly 12-14%.

For example, a 420-watt monocrystalline panel operating at 65°C might see its output temporarily reduced to about 365 watts. A 350-watt polycrystalline panel under the same conditions, with a common coefficient of -0.40%/°C, would drop to about 294 watts.

The price premium has also narrowed significantly, with monocrystalline modules now often costing between 1.00 and 1.30 per watt before installation. The durability is another key factor. Manufacturers provide robust warranties, typically guaranteeing 90% performance after 10 years and 82% to 85% after 25 years. This translates to an average annual degradation rate of only 0.3% to 0.5%, ensuring your investment continues to pay dividends for decades.

Polycrystalline

While a premium monocrystalline panel might boast an efficiency rating above 22%, a standard polycrystalline panel typically operates at between 16% and 17% efficiency. This means that for the same physical size—a standard panel of about 1.6 meters by 1 meter—a polycrystalline model will produce around 320 to 340 watts of power, compared to 380 to 420 watts from a high-end monocrystalline panel. The key advantage is cost: polycrystalline panels are generally 0.10 to 0.20 cheaper per watt. For a standard 10-kilowatt (kW) home system, this translates to an upfront saving of 1,000 to 2,000 on the cost of the panels alone, making solar power accessible to a wider range of households.

The lower cost is a direct result of a simpler manufacturing process. Instead of growing a single, pure silicon crystal, manufacturers melt multiple fragments of silicon together in a square mold. This process is faster, uses almost all the raw silicon material (reducing waste), and requires less energy.

Key Cost Drivers:

· Silicon Purity: Lower purity requirements for the silicon feedstock reduce material costs by approximately 15-20%.

· Manufacturing Yield: The simpler crystallization process leads to a higher yield and fewer production failures, increasing factory output by an estimated 10%.

· Energy Consumption: The process consumes about 25% less energy per cell compared to growing single-crystal ingots.

When comparing performance under real-world conditions, it's important to look beyond the nameplate efficiency. Like all silicon panels, polycrystalline output decreases as temperature rises. Their temperature coefficient is typically around -0.39% to -0.43% per degree Celsius, which is slightly higher (worse) than the -0.30% to -0.35% common for monocrystalline panels. On a hot day where panel temperatures reach 65°C (149°F), a 330-watt polycrystalline panel might see its output drop by roughly 14-16%, resulting in about 280 watts of actual power. Durability, however, is excellent. Polycrystalline panels come with the same robust 25-year performance warranties as their monocrystalline counterparts, with a guaranteed power output of around 82-85% at the end of the warranty period, correlating to an average annual degradation rate of about 0.5-0.6%.

Thin-Film

While crystalline silicon panels typically operate at 16-24% efficiency, mainstream thin-film panels, such as those made from Cadmium Telluride (CdTe), achieve efficiencies between 10% and 13%. This means a thin-film panel of the same physical dimensions as a standard 1.6m x 1m silicon panel might only produce 180-230 watts. Consequently, you might need twice the roof area to generate the same amount of power as a monocrystalline system. The primary advantage lies in the cost and application flexibility, with thin-film modules often costing 20-30% less per watt at the factory level, around 0.70 to 0.90 for the panel itself.

Common Thin-Film Materials:

· Cadmium Telluride (CdTe): This is the most prevalent type, holding over 50% of the thin-film market. It offers the lowest cost per watt and modules typically have efficiencies in the 10-13% range.

· Amorphous Silicon (a-Si): An early thin-film technology, a-Si is less efficient (6-9%) but is more environmentally benign. It also suffers from higher degradation in the first few months of exposure to sunlight, known as the Staebler-Wronski effect, which can cause an initial output drop of 10-15%.

· Copper Indium Gallium Selenide (CIGS): This material offers the highest efficiency potential for thin-film, with laboratory cells exceeding 23% and commercial panels reaching 14-16%.

Where thin-film truly shines is in its performance under non-ideal conditions. It has a significantly better temperature coefficient than silicon, typically around -0.20% per degree Celsius. On a 40°C (104°F) day, when silicon panel efficiency drops noticeably, a thin-film panel's output will decrease by 20-30% less than a crystalline panel. They also handle partial shading and diffuse light (like on cloudy days) more effectively, experiencing a lower percentage of power loss when a small section is covered.

Compare Factors

A panel with a slightly lower sticker price but significantly lower efficiency might end up costing you more over 25 years if it fails to meet your energy goals. The following table provides a crisp, data-driven snapshot of how the three main technologies stack up across the most critical decision-making criteria.

Factor | Monocrystalline | Polycrystalline | Thin-Film (CdTe) |

Average Module Efficiency | 22.5% | 16.5% | 11.5% |

Installed Cost per Watt (Range) | 2.80−3.40 | 2.60−3.20 | 2.30−2.90 |

Space for a 10 kW System | ~52 m² (560 sq ft) | ~62 m² (667 sq ft) | ~85 m² (915 sq ft) |

Temperature Coefficient (Power Loss/°C >25°C) | -0.30% | -0.41% | -0.21% |

Annual Power Degradation (Year 2 onwards) | 0.40% | 0.55% | 0.45% |

Typical Product/Performance Warranty | 25-30 years | 25 years | 10-15 years |

Monocrystalline panels command a price premium of roughly 0.20 to 0.30 per watt installed compared to polycrystalline, but they generate ~20% more power per square foot. This means that for a homeowner with limited, high-value roof space, monocrystalline is almost always the correct economic choice. The higher energy density allows you to install a system that meets 100% of your annual electricity consumption, which might be physically impossible with less efficient panels.

For a 10 kW system, the space savings of ~15 square meters is equivalent to a full parking spot, a critical advantage on smaller roofs. Conversely, if your available roof area is large and unshaded, the 5-8% lower total installation cost of a polycrystalline system can provide a faster return on investment without sacrificing your annual energy production target.

In a hot climate like Phoenix, where solar panel operating temperatures can consistently exceed 60°C (140°F), the difference in output loss is substantial. A monocrystalline panel's output will drop by approximately 10.5%, a polycrystalline panel's by about 14.4%, but a thin-film panel's by only 7.4%. This 4-7 percentage point advantage for thin-film in high heat can narrow the annual energy production gap with silicon panels by 3-5%.

Pick Your Best Fit

The "best" panel isn't a one-size-fits-all product; it's the one that optimally balances your roof's physical characteristics, your financial constraints, and your local climate to maximize your return over the system's 25-year lifespan. The decision matrix below simplifies this complex choice. For example, a homeowner in Arizona with a large, simple roof might prioritize heat tolerance and lower cost, making thin-film a surprising contender, while someone in New England with a small, complex roof will find that monocrystalline panels deliver the highest annual output despite the higher initial price tag of 1.10 to 1.40 per watt for a full installed system.

Your Primary Consideration | Recommended Panel Type | Key Rationale & Data Points |

Maximizing Power in Limited Space | Monocrystalline | With efficiencies of 22-24%, you need ~20% less roof area than with polycrystalline to generate the same 10 kW of power. The higher initial cost is offset by greater energy production per square meter. |

Achieving the Lowest Upfront Cost | Polycrystalline | At 0.85−1.05 per watt for the modules, a 10 kW system saves 1,500−3,000 on equipment costs versus monocrystalline. Ideal if you have ample, unshaded roof space. |

Large Commercial Roof / High-Theat Climate | Thin-Film (CdTe) | A temperature coefficient of -0.20%/°C means ~40% less power loss in heat versus polycrystalline. Lower weight (50% less per square foot) avoids structural reinforcement costs. |

Long-Term Warranty & Proven Durability | Monocrystalline | Standard 25-30 year product and performance warranties, with a slower annual degradation rate of ~0.4%, guarantee 85-90% performance after 25 years. |

To make a truly informed decision, you need to model the long-term financial outcome. This means looking beyond the simple cost per watt of the panels and calculating the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE). LCOE accounts for the total installed cost, minus incentives, divided by the total kilowatt-hours the system is projected to generate over its life.

A cheaper polycrystalline system might have a higher LCOE than a monocrystalline system if it produces significantly less energy due to shading or suboptimal orientation. For instance, if your roof faces east-west instead of south, the 15% lower efficiency of polycrystalline panels could result in an annual energy production deficit of 800-1,000 kWh compared to a monocrystalline array of the same size, extending your payback period by 1-2 years.

Your local weather patterns are a critical but often overlooked variable. If you live in a region that experiences high summer temperatures consistently above 30°C (86°F), the superior temperature coefficient of thin-film panels can significantly close the efficiency gap with silicon. On the other hand, if your location has a cooler climate with a high frequency of cloudy days, the superior low-light response and higher peak efficiency of monocrystalline panels will yield a greater energy harvest.