Do solar panels work through glass windows

Solar panels can generate power through glass, but efficiency usually drops by 10%-30%, with even higher losses for Low-E glass.

During operation, panels should be placed flush against single-layer transparent glass and face the sun directly, avoiding filmed or tinted glass to ensure efficient conversion.

Efficiency Loss

Not Much Electricity Left

Ordinary residential window glass usually adopts a soda-lime formula with an iron oxide content exceeding 0.1%.

This chemical composition causes the glass to appear slightly green and naturally absorbs about 15% to 18% of the incident solar spectrum.

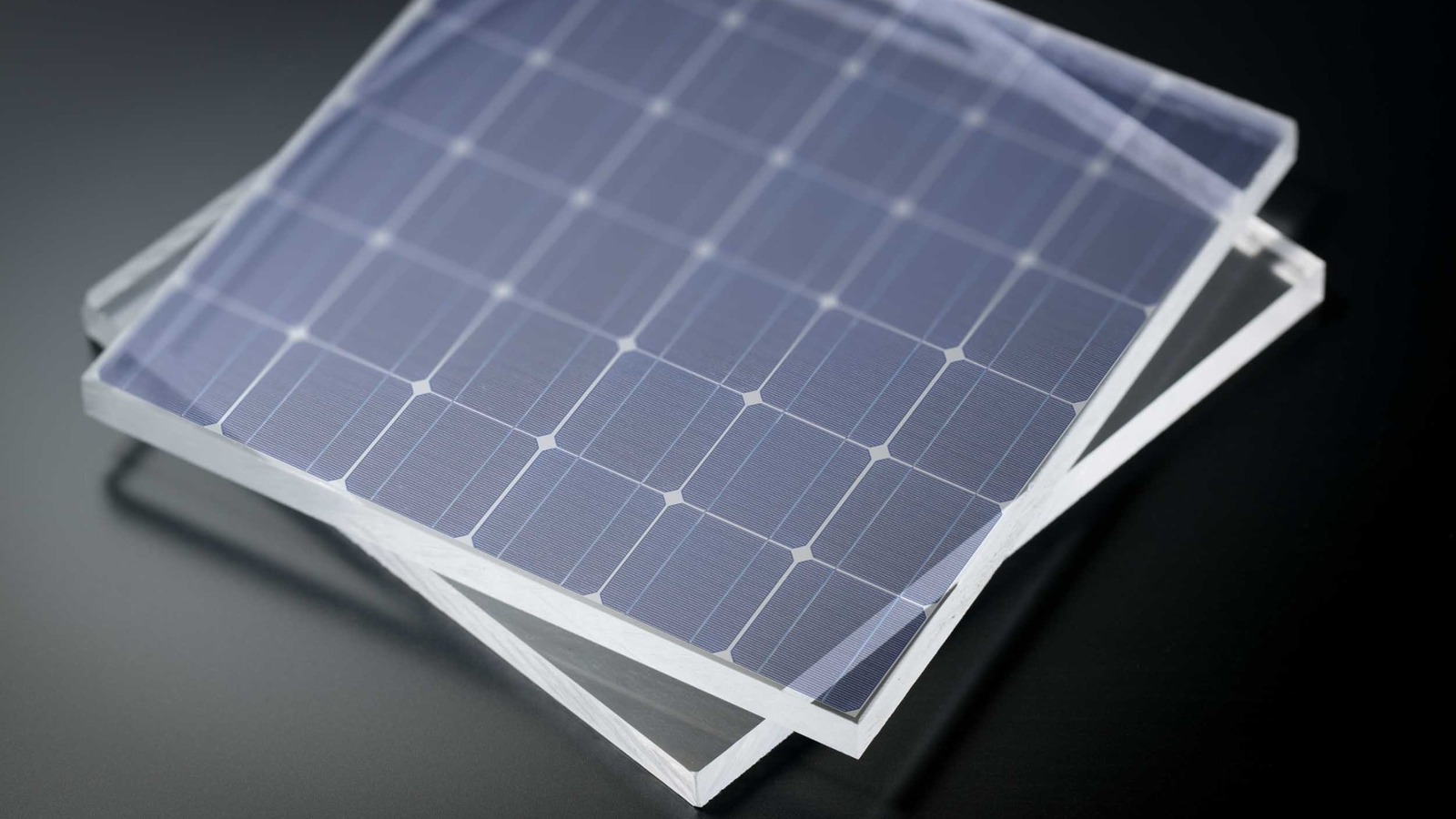

In contrast, the tempered glass covering the surface of solar panels is specially made low-iron glass, with iron content controlled below 0.02%, allowing 91.5% of photons to penetrate without obstruction and reach the silicon wafers.

When you place a solar panel with a rated power of 400 watts behind standard single-pane glass, the luminous flux density drops instantly from 1000 watts per square meter outdoors to 820 watts per square meter.

If your window is configured with double-pane insulated glass, the light must pass through two 5mm thick glass substrates and a 12mm argon gas layer between them.

This causes the light transmission rate to drop below 70% even under ideal vertical incidence conditions.

Your equipment has already lost 30% of its potential energy input at the starting line, and this is only the first hurdle brought by physical obstruction.

Silicon-based solar cells mainly rely on visible and near-infrared light with wavelengths between 380 nm and 1100 nm to excite electrons and generate current. However, ordinary window glass is designed to block over 95% of ultraviolet rays with wavelengths below 350 nm to prevent indoor furniture from fading, cutting off about 3% of the energy source.

Even more fatal is the Low-E (Low Emissivity) coating technology widely used in modern buildings.

This coating, composed of multiple nanoscale layers of silver or tin oxide, is designed to reflect long-wave infrared thermal energy.

A window with a Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) of 0.30 forcibly rejects 70% of solar heat energy, which directly leads to a 60% to 70% plunge in the solar panel's short-circuit current (Isc).

Although the open-circuit voltage (Voc) may only drop by about 5% due to its logarithmic relationship with light intensity, the power calculation formula is voltage multiplied by current.

For a 100-watt portable solar panel priced at $200, the actual output behind Low-E glass rarely exceeds 25 watts, which effectively quadruples the equipment cost per watt.

The refractive index of glass is about 1.52, while that of air is 1.00. This difference in medium density causes Fresnel reflection when light hits the glass surface.

When sunlight hits vertically at 90 degrees, the reflection loss is about 4%.

However, most windows are installed vertically, while the solar altitude angle in summer is usually above 60 degrees, making the incident angle of light often exceed 60 degrees.

According to the laws of optical physics, when the incident angle reaches 75 degrees, the reflectivity of the glass surface will soar from 4% to over 30%.

A large number of photons will be bounced off directly, like hitting a mirror.

If you test at 10 AM or 4 PM, when the angle between the sunlight and the window plane is very small, more than 55% of the solar radiation energy cannot enter the room at all.

This compresses the original eight hours of effective power generation time per day to less than three hours.

Placing the solar panel flush against the window creates a closed heat stagnation zone. The temperature of the 2 to 5 cm air layer between the panel and the glass can easily climb to 60°C or even 70°C under sunlight.

Crystalline silicon cells have a negative temperature power coefficient, usually around -0.45% per degree Celsius. For every 1 degree increase in temperature, the power generation efficiency drops by 0.45%.

A module that can output 18 volts under standard test conditions (25°C) will lose 22.5% of its voltage due to a 50-degree temperature rise when the operating temperature reaches 75°C, falling to around 14 volts.

For a 12-volt lead-acid or lithium cell charge controller that requires 14.4 volts to initiate the charging program, this voltage collapse causes the charging process to stop completely, even if the solar panel appears to be in direct sunlight.

This thermal effect not only reduces current output but also accelerates the aging of the EVA encapsulation material in a long-term high-temperature environment above 70°C, shortening the original 25-year module life to less than 10 years.

Calculating a 20% loss in glass light transmittance, a 25% loss in angular reflection, and a 20% efficiency decay due to high temperature, the overall conversion efficiency of the system usually only reaches about 35% of the outdoor standard value.

A balcony photovoltaic system originally designed to generate 2000 Wh of electricity per day may only have an actual daily output of 700 Wh when operating behind glass.

Compared to a utility electricity price of $0.15 per kWh, the payback period for this system will be infinitely extended from a reasonable 5 years to over 15 years, completely losing its economic viability.

Heat and Ventilation Issues

Compounded Heat Accumulation

Standard monocrystalline silicon solar panels are essentially huge black heat absorbers, with surface colors designed to absorb more than 95% of the visible light spectrum.

When the solar panel is placed in a well-ventilated outdoor environment, natural wind speeds usually remain between 2 to 4 meters per second.

Convective heat dissipation effectively keeps the panel's operating temperature within the range of ambient temperature plus 20°C.

However, once you move the panel indoors and place it flush against a glass window, you artificially create an extreme greenhouse effect trap.

Common residential window glass is opaque to thermal radiation with wavelengths above 3 microns.

High-energy photons from sunlight enter the room, are absorbed by the panel, and converted into thermal energy.

When this heat attempts to radiate outward as long-wave infrared rays, it is completely bounced back by the glass.

At noon, out of the 1000 watts per square meter of incident energy, only about 150 to 180 watts are converted into electricity, while the remaining 800+ watts are all converted into heat and trapped in the narrow 2 cm to 5 cm air gap between the panel and the window glass.

In the absence of forced air convection, the temperature of this stagnant air layer will skyrocket within 30 minutes.

Actual measurement data shows that when the outdoor temperature is 30°C, the back temperature of a solar panel placed against a window can easily exceed 75°C, even touching the dangerous red line of 85°C under extreme sunlight.

This is 30 to 40 degrees Celsius higher than the temperature of a module working in an outdoor ventilated environment at the same time.

Insufficient Voltage

Silicon-based semiconductor materials are extremely sensitive to temperature. Their physical properties dictate that for every 1°C increase in temperature, the open-circuit voltage (Voc) will drop by about 0.3% to 0.5%.

In a standard 18-volt solar module system, this negative temperature coefficient effect is lethal.

Under standard test conditions (25°C), the module's operating voltage (Vmp) might stabilize at 18.5 V, enough to easily drive the charging cycle of a 12 V cell system.

However, when the panel temperature climbs to 80°C due to poor ventilation, the 55-degree temperature rise causes a voltage loss of about 2.5 V to 3.5 V.

At this point, the actual output voltage of the panel may drop to the marginal area of 15V or even 14.5V.

For most cheap charge controllers based on Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) technology, the panel voltage must be kept at least 1V to 2V higher than the cell voltage to prevent reverse current flow.

When the thermal effect causes the panel voltage to plummet near the cell voltage, the controller will judge the input source invalid and cut off the charging circuit.

This explains why many users find that even though the sunlight is extremely strong and the panel is too hot to touch, the charging power displays as zero.

Parameter | Outdoor Ventilated (25°C Ambient) | Behind Glass Sealed (25°C Ambient) | Change Magnitude |

Module Operating Temp | 45°C - 50°C | 75°C - 85°C | +35°C |

Voltage Loss Rate | -8% (vs. Nominal) | -22% (vs. Nominal) | 2.7x Increase in Loss |

Power Output Efficiency | 90% (Considering line loss) | 65% (Heat loss only) | Plummeted |

Charge Current (100W Panel) | 5.2 Amps | 3.1 Amps | -40% |

EVA Film Lifespan | 25 Years | 5 - 8 Years | 3x Reduction |

Yellowing of the Film

Long-term high-temperature baking not only affects current power generation performance but also causes irreversible physical damage.

Solar cells are usually encapsulated between two layers of ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) film.

The optimal operating temperature range for this polymer material is below 60°C.

When exposed long-term to an oven-like environment above 80°C, the EVA material undergoes chemical degradation, producing acetic acid molecules.

This acidic substance slowly corrodes the silver grid electrodes on the cell surface, leading to an increase in series resistance (Rs).

A more intuitive manifestation is the rise of the yellowing index.

The transparent film will gradually turn scorched yellow under high temperatures, which further obstructs light transmittance, potentially leading to an additional 1% to 3% power attenuation per year.

According to the IEC 61,215 damp-heat test standard, continuous operation at 85°C makes the module age more than 10 times faster than at room temperature.

Photovoltaic modules with an original design life of 25 years, if "roasted" behind an unventilated window for a long time, may have their effective service life drastically shortened to 5 to 8 years, after which they will be completely scrapped due to delamination or internal circuit opens.

Risk of Shattering

When a black solar panel is placed flush against window glass, it acts as a local heat source heating the central area of the glass, causing the temperature of that area to rise above 50°C.

However, the edges of the glass covered by the window frame and the parts not covered by the solar panel may still maintain a temperature of around 25°C.

This uneven temperature distribution caused by local shading and heating creates huge thermal stress inside the glass.

For ordinary annealed float glass (non-tempered glass), once the temperature difference (Delta T) between points on the glass surface exceeds 30 to 40 degrees Celsius, the resulting tensile stress is enough to exceed the tensile strength of the glass, leading to thermal shattering.

A crack running through the entire window not only destroys the window's airtightness and esthetics but also incurs a replacement cost for a double-pane insulated window, usually between $300 and $500.

Forced Cooling

If you must use solar panels behind glass, you must manually establish heat dissipation channels.

The most effective passive solution is to move the solar panel back from the glass surface, leaving a gap of at least 15 cm to 20 cm, and ensuring no obstructions at the top or bottom of the panel so cold air can enter from the bottom and hot air can flow out from the top, forming a natural chimney effect.

Although this will lead to light scattering loss due to the increased distance, it is the lesser of two evils compared to the voltage collapse brought by high temperatures.

A more aggressive solution is to install 12V PC case fans on the back of the solar panel for forced air cooling.

This can usually suppress the operating temperature by 15°C and restore about 10% of the power output.

However, the fan itself will consume 2 to 5 watts of power.

Angle of Incidence

Self-Defeating Reflection

In physical optics, when light hits a photovoltaic panel surface vertically at 90 degrees, the photon penetration rate is highest and the reflectivity is lowest.

However, once you place the solar panel behind a fixed vertical window, you almost completely relinquish control over the incident angle.

Most residential windows are vertical to the ground, i.e., at a tilt angle of 90 degrees.

Taking regions at 40 degrees north latitude (such as New York, Madrid, or Beijing) as an example, the solar altitude angle at noon in summer is usually as high as 73 degrees.

Sunlight shines down almost vertically from overhead. When these rays hit a vertical glass window, their angle with the glass surface normal is as high as 73 degrees.

According to Fresnel equations, when the incident angle exceeds 60 degrees, the reflectivity of the glass surface does not stay at a low 4%, but instead soars exponentially.

· 0° to 45° Incident Angle: Glass reflectivity stays around 4% to 5%; most light can pass through.

· 60° Incident Angle: Reflectivity starts to climb to around 10%.

· 75° Incident Angle: Reflectivity sharply explodes to 30% - 40%.

· 85° Incident Angle: Reflectivity exceeds 70%. At this point, the window glass is almost like a mirror to sunlight, and most energy is bounced off directly.

Only Two Hours of Exposure

Outdoors, solar panels with tracking mounts or even those fixed at the optimal tilt (usually the local latitude) can maintain relatively efficient output from 9 AM to 4 PM, with about 5 to 6 "Peak Sun Hours" per day.

But behind a vertical window, the situation is completely different. For a south-facing window in summer, because the sun is positioned extremely high, light "brushes" across the glass surface at a huge angle for most of the time.

Only during a short period before 9 AM and after 5 PM, or at noon in winter when the solar altitude angle is lower (about 26°), is the incident angle relatively ideal.

Actual measurement data shows that the total solar radiation (Insolation) received throughout the day by a solar panel placed vertically indoors is usually only 25% to 30% of a panel at the optimal outdoor angle.

Even for a 100-watt rated panel, under such angular restrictions, the accumulated power generated throughout the day may be less than 150 Wh, which isn't even enough to fully charge the cell of a 13-inch laptop.

Blocked Completely by Shadows

Photovoltaic modules are usually composed of 32, 60, or 72 single cells in series. This series circuit is like old-fashioned Christmas tree lights; the current channel is also the weakest link.

If window frames, mullions, security bars, or tree branches outside cast shadows covering even 10% of the area on the solar panel, the current output of the entire module will be limited by the "barrel effect," dropping directly to the current level of the shaded cell.

If one cell is completely shaded, the current of the entire series circuit may instantly drop near zero.

Although modern photovoltaic modules are equipped with bypass diodes to circumvent damaged areas, activating a diode sacrifices about 33% of the voltage output of that cell string.

Indoors by the window, shadows are dynamic and unpredictable as the sun's angle changes.

· Window Frame Shading: When light hits at an oblique angle in the morning and evening, the window frame deeply set in the wall will cast a thick shadow several centimeters wide on the glass, which is often enough to cover an entire row of cells.

· Screen Interference: Many homes are equipped with mosquito screens. This dense mesh not only reduces light intensity by 30% to 50% but also produces a diffuse reflection effect similar to cloud shading, completely disrupting the direct path of light.

· Glass Thickness: When light enters at a 70-degree angle, its actual propagation path in 5mm thick glass will stretch to more than 15mm. This increases the probability of photons being absorbed by impurities (such as iron ions) in the glass, further reducing the number of photons reaching the silicon wafer.

Brackets Won't Help Much

Some try to use tripods or brackets indoors to tilt the solar panel to be perpendicular to the incident sunlight, attempting to cheat the laws of physics.

While this indeed solves the angular problem (cosine loss) between the solar panel and the light after it passes through the glass, allowing the panel to receive indoor light at 90 degrees, it does not solve the first hurdle.

No matter how you adjust the panel's angle indoors, the high reflection loss at the moment sunlight passes through the window glass has already occurred and is irreversible.

Furthermore, tilting a panel indoors often requires it to be moved some distance away from the window glass, which reduces the projected area and makes it more susceptible to shading from indoor furniture and curtains.

Better in Winter Instead

In the Northern Hemisphere, in winter, the sun's path in the sky is lower.

For example, around the winter solstice, the noon solar altitude angle may only be 25 to 30 degrees.

At this time, the incident angle of sunlight hitting vertical glass is about 60 to 65 degrees, which is much better than the 75 degrees in summer.

Light can penetrate deeper into the room and hit a more vertical surface.

This is also one of the principles of passive solar house design: block high-angle sunlight in summer to prevent overheating and invite low-angle sunlight in winter for heating.

For those users counting on power generation through windows, the generation efficiency is actually worst during the hot summer air-conditioning peak when electricity is most needed.

Efficiency only recovers slightly during winter days when power demand is relatively lower, but winter daylight hours are 4 to 5 hours shorter than in summer.